FactorizePhys: Matrix Factorization for Multidimensional Attention in Remote Physiological Sensing

Matrix Factorization as Attention - Rethinking Multidimensional Feature Processing in Remote Physiological Sensing

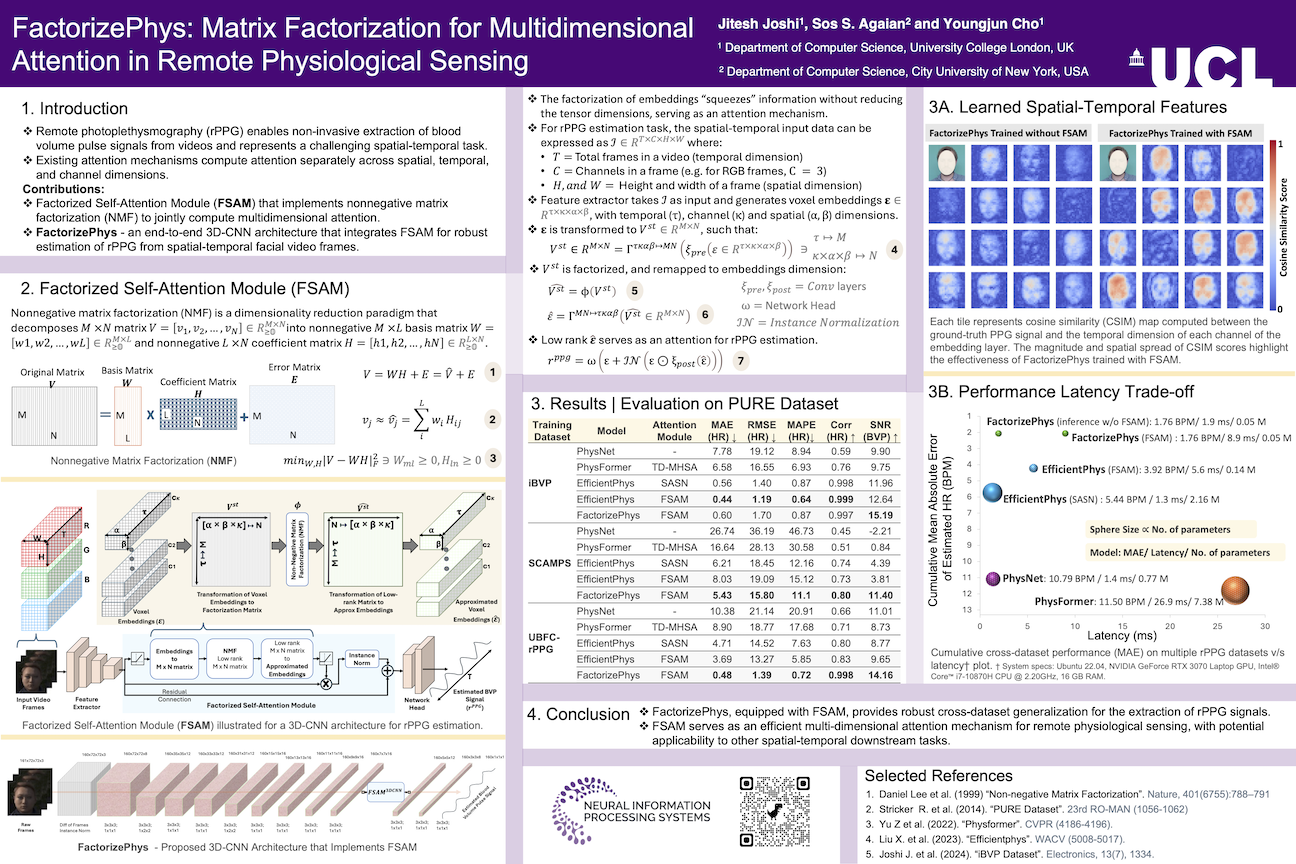

We presented our work - FactorizePhys [1], that focuses on remote photoplethysmography (rPPG), at NeurIPS 2024, held at Vancouver, Canada during 10th to 14th December. The conference was extremely memorable, and our work was appreciated by several attendees who visited our poster session. Some obvious queries from fellow researchers stressed why not use transformer networks, when cross-attention has been the backbone of LLM advancements. Researchers even attempted to draw parallels with cross-attention formulation to understand our proposed matrix factorization-based multidimensional attention (FSAM), with their key concern being: how can factorization serve as attention?

Here, we explore the rationale behind matrix factorization-based attention mechanisms and how they differ from self-attention/ cross-attention/ transformers.

Figure 1: Our poster at NeurIPS 2024, where we discussed FSAM with fellow researchers from the computer vision and machine learning community.

The Compression-as-Attention Paradigm

Using compression as an attention mechanism isn’t new. In the CNN-dominated era, squeeze-and-excitation (SE) attention [2] was among the most popular mechanisms. SE attention works by globally average pooling across spatial dimensions to compress features into channel descriptors, then using fully connected layers to model channel interdependencies, and finally rescaling the original features.

However, a fundamental limitation emerges when working with multidimensional feature spaces: existing attention mechanisms compute attention disjointly across spatial, temporal, and channel dimensions. For tasks like rPPG estimation that require joint modeling of these dimensions, squeezing individual dimensions can result in information loss, causing learned attention to miss comprehensive multidimensional feature relationships.

This is precisely the problem our work addresses.

FSAM: Factorized Self-Attention Module

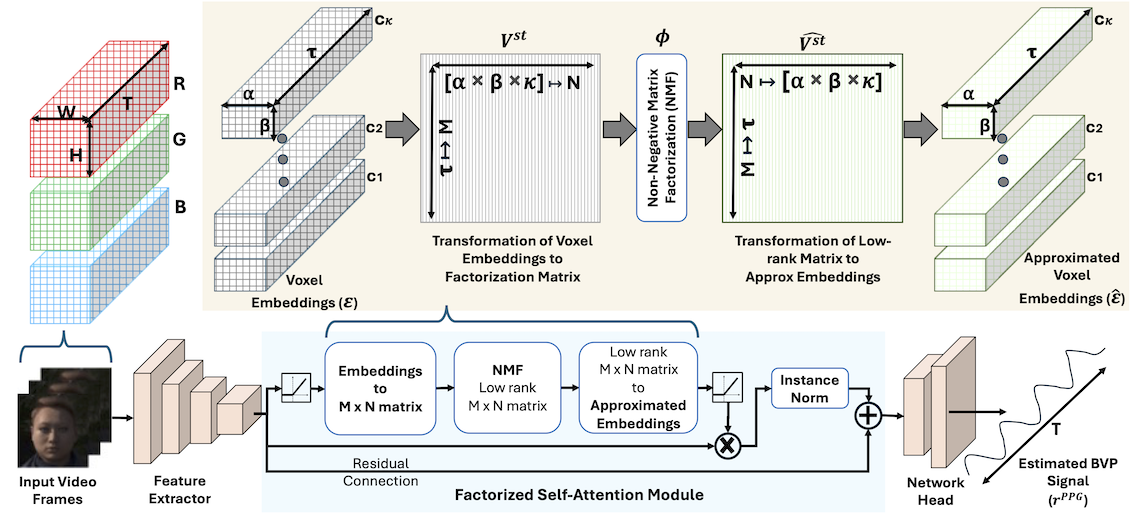

FSAM uses Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) [3] to factorize multidimensional feature space into a low-rank approximation, serving as a compressed representation that preserves interdependencies across all dimensions. The key advantages are:

- Joint multidimensional attention - No dimension squeezing required; processes spatial, temporal, and channel dimensions simultaneously

- Parameter-free optimization - Uses classic NMF as proposed by Lee & Seung, 1999 [3], with an optimization algorithm approximated as multiplicative updates [4], implemented under ‘no_grad’ block

- Task-specific design - Tailored for signal extraction tasks with rank-1 factorization

Figure 2: Overview of the Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) showing how multidimensional voxel embeddings are transformed into a 2D matrix, factorized using NMF, and reconstructed to provide attention weights.

Mathematical Formulation

The Critical Transformation

Input spatial-temporal data can be expressed as \(\mathcal{I} \in \mathbb{R}^{T \times C \times H \times W}\), where \(T,~C,~H,~and~W\) represents total frames (temporal dimension), channels in a frame (e.g., for RGB frames, \(C=3\)), height and width of pixels in a frame, respectively. For this input \(\mathcal{I}\), we generate voxel embeddings \(\varepsilon \in \mathbb{R}^{\tau \times \kappa \times \alpha \times \beta}\) through 3D feature extraction. The core innovation lies in how we reshape these embeddings for factorization.

Traditional 2D approach (like Hamburger module [4]):

\[V^{s} \in \mathbb{R}^{M \times N} = \Gamma^{\kappa\alpha\beta \mapsto MN}(\xi_{pre}(\varepsilon \in \mathbb{R}^{\kappa \times \alpha \times \beta})) \ni \kappa \mapsto M,\alpha \times \beta \mapsto N\]where, \(\kappa (channels) → M, \alpha \times \beta (spatial) → N\), and \(\xi_{pre}\) represents preprocessing operation.

Our 3D spatial-temporal approach:

\[V^{st} \in \mathbb{R}^{M \times N} = \Gamma^{\tau\kappa\alpha\beta \mapsto MN}(\xi_{pre}(\varepsilon \in \mathbb{R}^{\tau \times \kappa \times \alpha \times \beta})) \ni \tau (temporal) \mapsto M, \kappa \times \alpha \times \beta (spatial+channel) \mapsto N\]This transformation is crucial for rPPG estimation because:

- Physiological signal correlation: We need correlations between spatial/channel features and temporal patterns for BVP signal recovery

- Single signal source: Only one underlying BVP signal across facial regions justifies rank-1 factorization ($L=1$)

- Scale considerations: Temporal and spatial dimensions have vastly different scales (typically $ε » ϖ, ϱ$ for video data)

The NMF Attention Mechanism

The factorization process uses iterative multiplicative updates:

def fsam(E)

S = 1

rank = 1

MD_STEPS = 4

ε = 1e-4

batch, channel_dim, temporal_dim, alpha, beta = E.shape

spatial_dim = alpha x beta

# Preprocessing: ensure non-negativity for NMF

x = ReLU(Conv3D(E - E.min()))

# Transform to factorization matrix

V_st = reshape(x, (batch × S, temporal_dim, spatial_dim × channel_dim))

# Initialize bases and coefficients

bases = torch.ones(batch × S, temporal_dim, rank)

coef = softmax(V_st^T @ bases)

# Iterative multiplicative updates (4-8 steps)

for step in range(MD_STEPS):

# Update coefficients

numerator = V_st^T @ bases

denominator = coef @ (bases^T @ bases)

coef = coef ⊙ (numerator / (denominator + ε))

# Update bases

numerator = V_st @ coef

denominator = bases @ (coef^T @ coef)

bases = bases ⊙ (numerator / (denominator + ε))

# Reconstruct attention

V̂_st = bases @ coef^T

Ê = reshape(V̂_st, (batch, channel_dim, temporal_dim, alpha, beta))

# Apply attention with residual connection

output = E + InstanceNorm(E ⊙ ReLU(Conv3D(Ê)))

return output

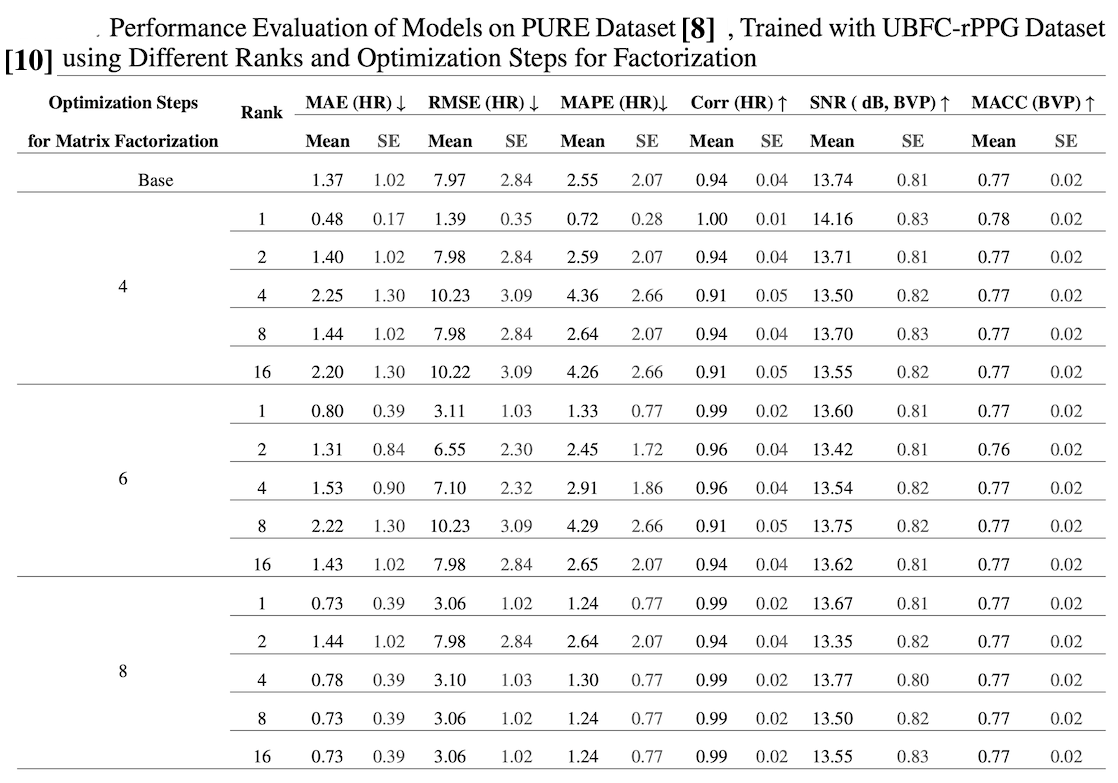

Why Rank-1 Factorization Works

The paper’s ablation studies confirm that rank-1 factorization performs optimally for rPPG estimation. This aligns with the physiological assumption that there’s a single underlying blood volume pulse signal across different facial regions. Higher ranks (L > 1) showed performance comparable to the baseline without FSAM, indicating rank-1 captures the essential signal structure.

Table 1: Ablation study results showing performance across different factorization ranks. Rank-1 achieves optimal performance, supporting the single signal source assumption for rPPG estimation.

Why FSAM Outperforms Transformers

1. Task-Specific vs Generic Design

Transformers use generic self-attention that treats all positions equally:

\[Attention(Q,K,V) = softmax(QK^T/√d_k)V\]FSAM is specifically designed for spatial-temporal signal extraction:

- Temporal vectors as the primary dimension (signals evolve over time, and directly supervised through loss function)

- Spatial-channel features as descriptors (different facial regions contribute differently)

- Rank-1 constraint enforces single signal source assumption, though this may differ across downstream tasks and characteristics of the data

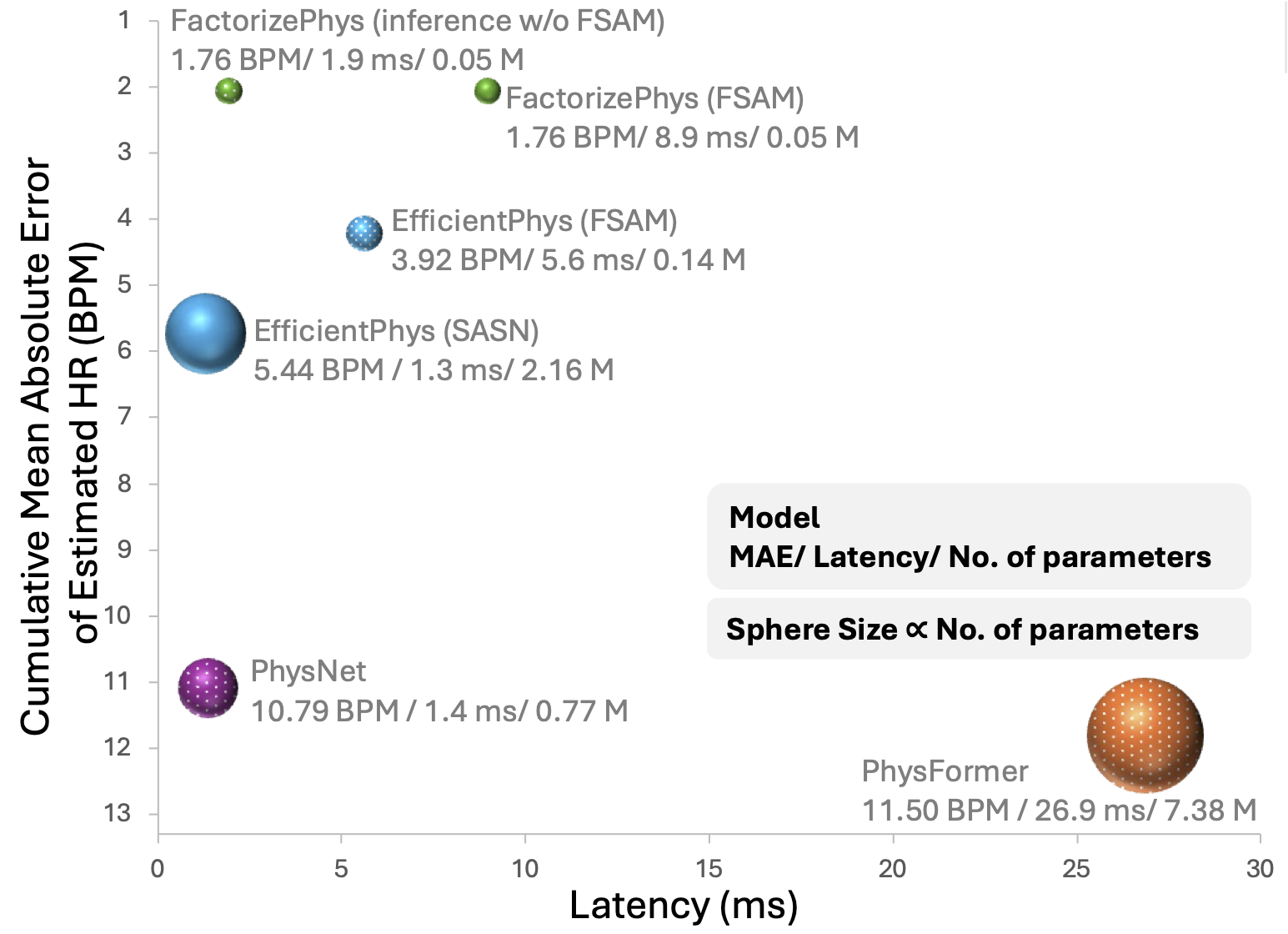

2. Computational Efficiency

- FSAM complexity: O(n) with 4-8 multiplicative update steps

- Transformer complexity: O(n²) with full attention computation [5]

- Parameter comparison: FactorizePhys (52K) vs PhysFormer (7.38M) - 138x fewer parameters

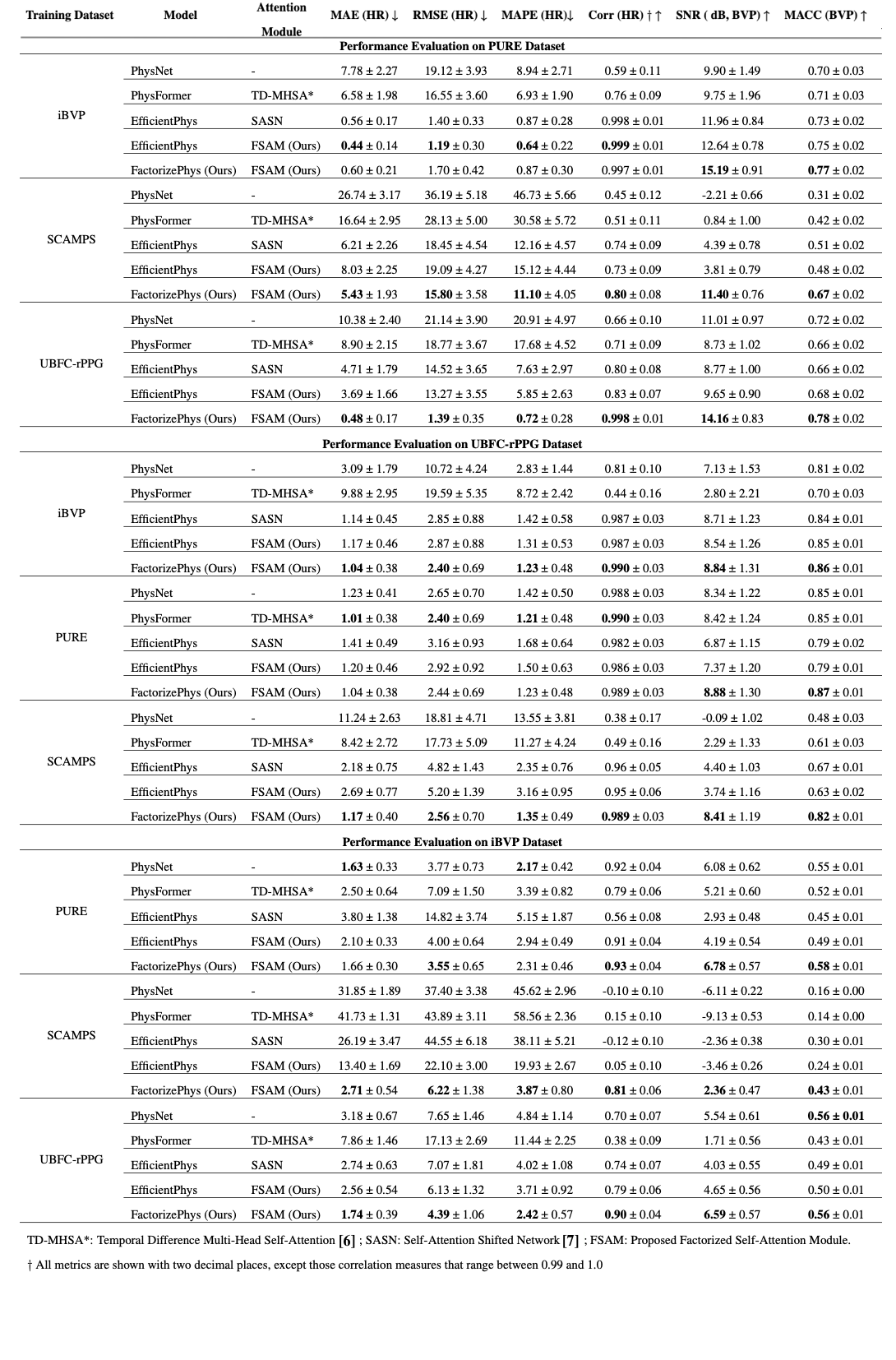

3. Superior Cross-Dataset Generalization

Table 2: Comprehensive evaluation across four datasets shows remarkable generalization

| Training → Testing | PhysFormer (MAE↓) | EfficientPhys (MAE↓) | FactorizePhys (MAE↓) |

|---|---|---|---|

| iBVP → PURE | 6.58 ± 1.98 | 0.56 ± 0.17 | 0.60 ± 0.21 |

| SCAMPS → PURE | 16.64 ± 2.95 | 6.21 ± 2.26 | 5.43 ± 1.93 |

| UBFC → PURE | 8.90 ± 2.15 | 4.71 ± 1.79 | 0.48 ± 0.17 |

Key insight: When trained on synthetic data (SCAMPS) and tested on real data, FactorizePhys shows the smallest performance gap, indicating superior domain transfer.

Table 3: Cross-dataset generalization performance comparison

FactorizePhys consistently outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods, including the transformer-based methods across different domain shifts, particularly in synthetic-to-real transfer scenarios.

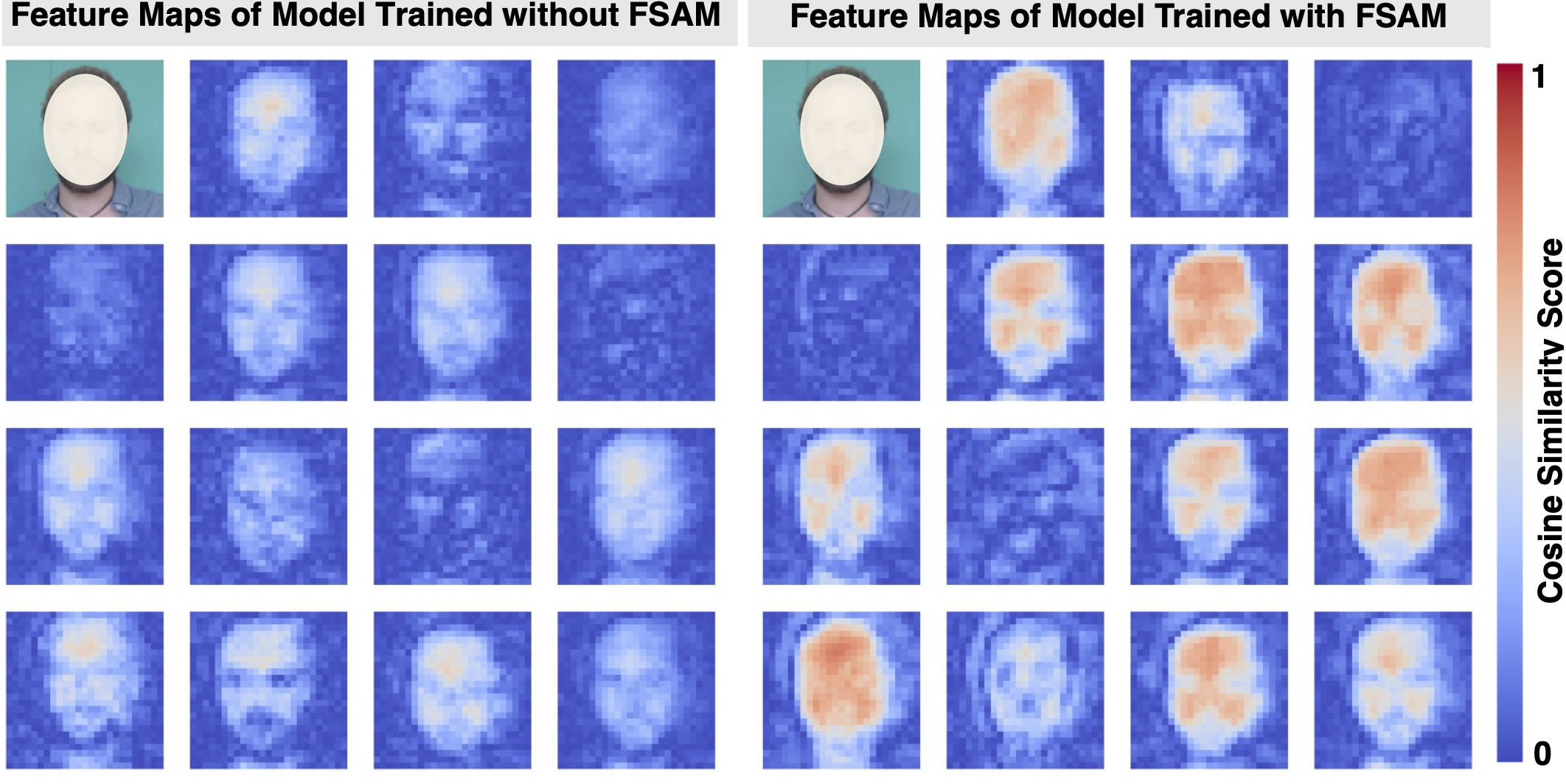

4. Attention Visualization

Our cosine similarity visualization between temporal embeddings and ground-truth PPG signals reveals:

- Higher correlation scores for FactorizePhys with FSAM

- Better spatial selectivity - correctly identifies skin regions with strong pulse signals

Figure 3: Attention visualization comparing baseline model (left) and FactorizePhys with FSAM (right). Higher cosine similarity scores (brighter regions) indicate better spatial selectivity for pulse-rich facial regions.

The Inference-Time Advantage

A surprising finding: FactorizePhys trained with FSAM retains performance even when FSAM is dropped during inference. This suggests FSAM enhances saliency of relevant features during training, guiding the network to learn such salient feature representations that persist without the attention module.

# Training: FSAM influences 3D convolutional kernels

factorized_embeddings = fsam(voxel_embeddings)

loss = compute_loss(head(factorized_embeddings), ground_truth)

# Inference: Can drop FSAM without performance loss

output = head(voxel_embeddings) # No FSAM needed!

This dramatically reduces inference latency while maintaining accuracy - ideal for real-time applications.

Figure 4: Performance vs. latency comparison showing FactorizePhys achieves superior accuracy with minimal inference time, especially when FSAM is dropped during inference.

Key Contributions and Broader Implications

For the rPPG Community

- First matrix factorization-based attention specifically designed for physiological signal extraction from facial videos

- State-of-the-art cross-dataset generalization with dramatically fewer parameters

- Real-time deployment capability without performance degradation

For the Broader AI Community

- Novel attention paradigm demonstrating that domain-specific designs can outperform generic mechanisms

- Efficiency breakthrough: 138x parameter reduction compared to transformers with superior performance

- New perspective on attention in deep-learing architecutures: Factorization as compression can be more effective than dimension squeezing

Looking Forward: Future Research Directions

FSAM’s success opens several promising avenues:

- Extended Applications: Video understanding, action recognition, time-series analysis

- Enhanced NMF Variants: Incorporating temporal smoothness or frequency domain constraints. Checkout our subsequent work (MMRPhys) that explores this direction for robust estimation of multiple physiological signals.

- Hybrid Architectures: Combining factorization-based attention with other mechanisms for different modalities

- Theoretical Analysis: Understanding why rank-1 factorization generalizes so well across datasets

Conclusion

The key insight is profound yet simple: not all tasks require the full complexity of transformer attention. For spatial-temporal signal extraction tasks, a well-designed, task-specific attention mechanism can achieve superior robustness with dramatically improved efficiency.

FSAM demonstrates that the deeper understanding the problem domain can lead to more effective solutions than applying generic, computationally expensive methods. In an era of ever-growing model sizes, this work shows that thoughtful design trumps brute-force scaling.

Code and Data Availability

| Resources | Link | |

|---|---|---|

| Paper | FactorizePhys | |

| Code | GitHub | |

| Dataset | iBVP Dataset |

References

[1] Joshi, J., Agaian, S. S., & Cho, Y. (2024). FactorizePhys: Matrix Factorization for Multidimensional Attention in Remote Physiological Sensing. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2024).

[2] Hu, J., Shen, L., & Sun, G. (2018). Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 7132-7141).

[3] Lee, D. D., & Seung, H. S. (1999). Learning the parts of objects by non-negative matrix factorization. Nature, 401(6755), 788-791.

[4] Geng, Z., Guo, M. H., Chen, H., Li, X., Wei, K., & Lin, Z. (2021). Is attention better than matrix decomposition? In International Conference on Learning Representations.

[5] Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., … & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 5998-6008).

[6] Yu, Z., Shen, Y., Shi, J., Zhao, H., Torr, P. H., & Zhao, G. (2022). PhysFormer: Facial video-based physiological measurement with temporal difference transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 4186-4196).

[7] Liu, X., Hill, B., Jiang, Z., Patel, S., & McDuff, D. (2023). EfficientPhys: Enabling simple, fast and accurate camera-based cardiac measurement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (pp. 5008-5017).

[8] Stricker, R., Müller, S., & Gross, H. M. (2014). Non-contact video-based pulse rate measurement on a mobile service robot. In The 23rd IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (pp. 1056-1062).

[9] McDuff, D., Wander, M., Liu, X., Hill, B., Hernandez, J., Lester, J., & Baltrusaitis, T. (2022). SCAMPS: Synthetics for camera measurement of physiological signals. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35, 3744-3757.

[10] Bobbia, S., Macwan, R., Benezeth, Y., Mansouri, A., & Dubois, J. (2019). Unsupervised skin tissue segmentation for remote photoplethysmography. Pattern Recognition Letters, 124, 82-90.

Citation:

@inproceedings{joshi2024factorizephys,

author = {Joshi, Jitesh and Agaian, Sos S. and Cho, Youngjun},

booktitle = {Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems},

editor = {A. Globerson and L. Mackey and D. Belgrave and A. Fan and U. Paquet and J. Tomczak and C. Zhang},

pages = {96607--96639},

publisher = {Curran Associates, Inc.},

title = {FactorizePhys: Matrix Factorization for Multidimensional Attention in Remote Physiological Sensing},

url = {https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2024/file/af1c61e4dd59596f033d826419870602-Paper-Conference.pdf},

volume = {37},

year = {2024}

}

This work was conducted at the Department of Computer Science, University College London, under the supervision of Prof. Youngjun Cho. Jitesh Joshi was fully supported with international studentship that was secured by Prof. Cho

For questions or collaborations, please contact: jitesh.joshi.20@ucl.ac.uk